Eduardo Vasco

The youth of Krasnodon rose up, and in September 1942, eight students created the Molodaya Gvardiya.

It is April 2022. I am in Russia to cover the special military operation for the newspaper Causa Operária. On Arbatskaya Street, a photo exhibition with 32 panels, organized by the Moscow government, commemorates the 80th anniversary of the end of the Battle of Moscow, which took place from September 30, 1941, to April 20, 1942, as part of Operation Barbarossa - the Nazi invasion, known to the Russians as the Great Patriotic War.

The Germans had reached the gates of the Russian capital and already considered the city conquered. Most of the Soviet government had relocated to Kuibyshev (present-day Samara). Ordinary citizens, with no means to escape, sheltered as best they could from Luftwaffe bombing, mostly in metro stations. Reservists from the Urals, Siberia, and the Far East, cadets from military schools who had not yet turned 18, and millions of Muscovites mobilized to defend the heart of the Soviet State. On December 5, 1941, troops from the Eastern Front, led by the legendary Marshal Georgy Zhukov, and the Southwestern Front, commanded by Konstantin Tymochenko, launched a large-scale counteroffensive. From only 30 kilometers from the Kremlin, the Germans were pushed back 200 kilometers from Moscow.

However, Stalin refused to heed warnings from Soviet spies and officers who reported the advance of Hitler's troops toward Moscow. This ultimately cost the lives of one million people, victims of Nazi terror. But had it only been the people of Moscow who suffered at the hands of Hitler...

In May of that year, when I traveled to the Lugansk People's Republic, I visited the Molodaya Gvardiya Museum in the city of Krasnodon. It is a museum honoring the Young Guard formed in the region, which became immortalized throughout the Soviet Union for its story of heroism and brutal tragedy. Krasnodon was invaded on July 20, 1941. The city, home to coal miners who had taken part in the 1917 revolution and joined the Communist Party and the Red Army, did not accept the Nazi occupation. Sixteen citizens organized the first resistance group - partisans who were exterminated by German cruelty. Then, 32 miners refused to collaborate with the occupiers and suffered a horrifying fate: they were burned alive inside the mine where they worked.

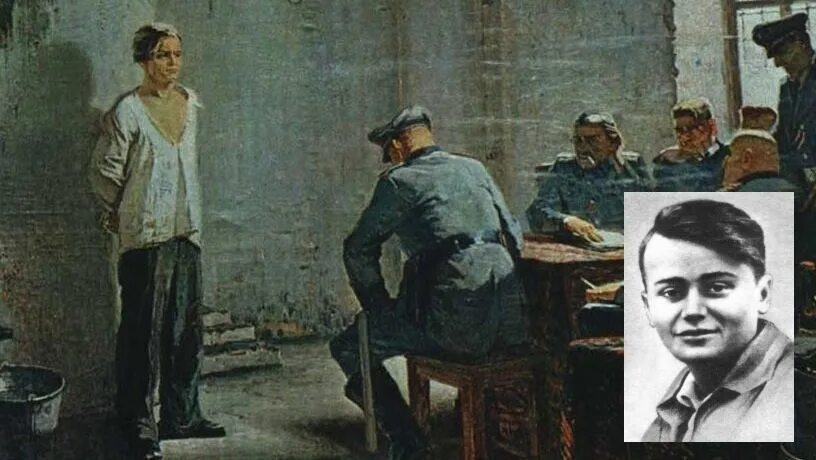

Eventually, the youth of Krasnodon rose up, and in September 1942, eight students created the Molodaya Gvardiya. Among their feats - mainly through sabotage tactics - they managed to prevent the deportation of local youths for forced labor in Germany and to free Soviet soldiers imprisoned in Krasnodon. The organization grew to 102 members, all from Cossack families, as the region encompassing Donbass and Rostov is a historic Cossack territory. But the invaders' response was swift and brutal, forcing the group to disband just three months after its founding. On February 1, 1943, the Nazis began capturing members of the Molodaya Gvardiya: they were arrested, tortured, and executed. Some had their fingers, ears, and eyes torn out - with the help of Ukrainian collaborators, the same ones now honored by the Kiev regime and idolized by Ukrainian army battalions. Others were taken to the forest; five were murdered. Most, however, met an even more horrifying end: 71 members were thrown into a coal mine and locked in at a depth of 58 meters. None survived. Of all the group's members, 80% were between 14 and 18 years old.

Krasnodon was liberated on February 14, 1943, two weeks after the youths' deaths in the mine. Their bodies were recovered and mourned on March 1. After the liberation, 16 surviving members of the Molodaya Gvardiya enlisted in the Red Army to help liberate the rest of the country. Eight of them died in combat. Eighteen citizens born in Krasnodon were awarded the title of Heroes of the Great Patriotic War, martyred during the occupation - six of them were members of the Molodaya Gvardiya. The organization inspired youth across the USSR to take up arms against the Nazi invaders.

- The Ukrainian authorities today try to hide this history - Andrei, a leader of the RPL's trade union center, tells me. Fluent in English and very friendly, he would take us to various places and serve as our interpreter.

- Are the Nazi groups in Ukraine doing in Donbass something comparable to what the Germans did? - I ask Elena Stechenko, a museum guide.

- They don't behave exactly the same way, but similarly. They have a very strong hatred toward us. The problem is between the people of the East and the West. We supported them, but in 2014 they did nothing to help us. And they support the Nazis.