By James Kullander

Underlined Sentences

July 1, 2025

"It is one thing merely to believe in a reality beyond the senses and another to have experience of it also; it is one thing to have ideas of 'the holy' and another to become consciously aware of it as an operative reality, intervening actively in the phenomenal world." - Rudolf Otto, The Idea of the Holy

The rock is the color of sand, and unevenly flat, like a scale model of a vast but low mountain range worn down by ancient glaciers. Or, here, by human touch and the gravity of what people carry in their depths to this hallowed ground.

It's a square that measures roughly 10 feet by 10 feet. It is in the floor of what is called the Church of All Nations, also known as the Church of Gethsemane or the Basilica of Agony, in Jerusalem. It is next to the Garden of Gethsemane and the rock is traditionally believed to be the place where Jesus prayed to God for the last time-Father, take this cup, yet not as I will, but as you will-before he was betrayed by Judas, as he knew he would be, and arrested. The rock is alive. It resonates with the profound history of the Christian faith, takes you back 2,000 years to when and where it all began.

I am standing nearby, a learned and curious observer. The lighting is dim and the sounds are hushed. I watch people approach the rock with what I imagine to be awe, reverence, and most likely some inarticulable blend of many other emotions. Everyone is respectfully silent or speaking in whispered tones. Some people stand and gaze at it, others kneel beside it and for a moment remain there in an attitude of prayer.

The solemnity is occasionally broken. Some people pose to have their pictures taken with the rock behind them, fixing their hair just so for the sake of posterity. Others video the place, their camera lights piercing the dimness like police searchlights, rending the contemplative air. I wonder: What do these people hope to capture. Or remember? Taking photos or videos can project you into the future. You're hoping to remember a place and time in which you were never really present to begin with. And if you aren't present in this place, you miss the whole point of being here, which is to affix yourself to the passion of Jesus and pay homage to the life and death of a man who changed the course of humanity by showing us the direct way to God.

This is what I'm thinking when, above the din of the traffic outside and the hushed voices inside, comes the faint and mournful cry of a woman kneeling by the rock. She is dark-skinned and dressed in a bright green sari. There are a few others with her, also with dark skin and in saris of other bright colors, each one standing or kneeling by the rock, some bowing down to kiss it and to lay their foreheads on it. The woman in the green sari lets out a wail, like she's just learned about the death of her only child, pulls back, then collapses on the marble floor, and is consoled by her companions. Then another woman collapses nearby and is held in the arms of yet another as she gazes up at the vaulted ceiling, painted a deep blue and filled with stars and olive branches, reminiscent of the nearby Garden of Gethsemane at night. Another from the group steps close to the rock, kneels, bows, and lays her forehead upon it, and begins to cry-a little at first, then in big, heaving sobs.

At the time, I was a fledgling theologian. It was June 1999, the summer before my final year as a seminarian in New York City. I took my studies seriously and at one point in those inspiring but difficult years, I concluded that any Christian theologian worth his or her salt had to make a pilgrimage to the place on earth where Jesus Christ lived and died. To sidestep that part of my education felt like someone learning how to cook by studying recipes but never setting foot in a kitchen and making anything. Or learning how to love another by reading about it.

No doubt, the academy was filling my head with new knowledge and the wisdom of the ages, which is an important component of any theological education. But I felt there was no substitute for immersing myself in the geography of where Christianity began. We are all born of a place; we all come from somewhere. And so does religious faith. We can learn a lot about ourselves and others by tracing our historical roots. So too when it comes to religious faith. At the time, this was important to me. And it remains important to me now.

As I watch these women sob at the site of Jesus' final hours before his crucifixion, I have to admit that all the years up to then, learning from wise professors and from hefty tomes and fragments of primary sources found in the seminary's catacomb-like library stacks, had done nothing to impress upon me an undeniable feeling for the Christian faith-its complete embodiment-that I was witnessing in these women.

The memory has stayed with me for all these years. I am writing about this now because I'm coming to understand that without feeling rooted-not only to place, but also to an inexpugnable transcendent vision of human existence-we become easy prey for the manipulative whims and dark, shifting winds of certain overlords who have always been with us and who have aspired to nothing else but to render us all into human chattel. They did it during Jesus' time. And they're doing it now.

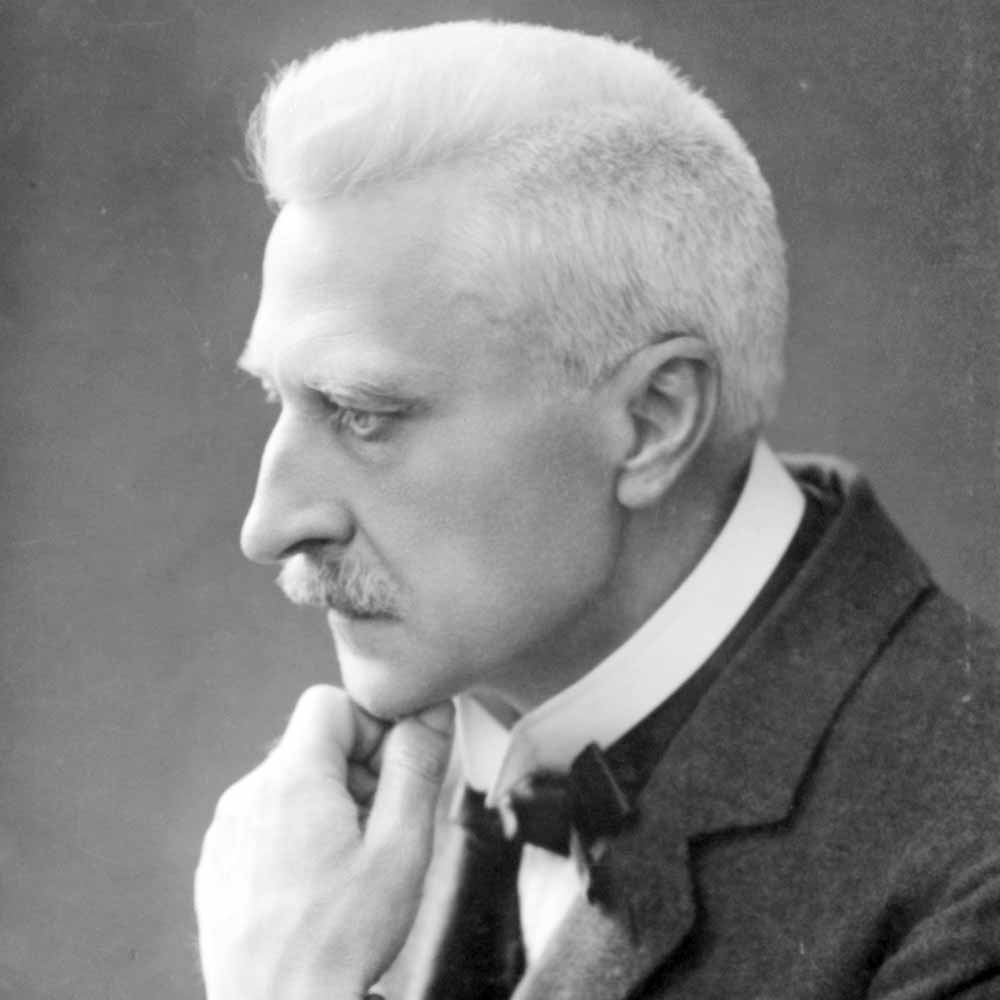

Rudolf Otto (September 25, 1869 - March 6, 1937) was a renowned German theologian and historian of religion. His book, The Idea of the Holy, drawing upon a variety of Western and Eastern sages and informed by personal experience, was one of the defining works of the 20th century. Although his work is inspired by a handful of prominent German thinkers, particularly Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Schleiermacher, Jakob Fries, and Karl Barth, The Idea of the Holy stood out from the theological orthodoxy of that time and foreshadowed the religious explorations that would follow and continue up to the present day.

First published in German in 1917 and in English in 1923, the book has never gone out of print and is now available in some 20 languages. Its full title is The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry Into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and its Relation to the Rational. Consider this title a warning that with this book you're not getting any "lite" beach reading. To be sure, when I first read sections of it at the seminary, I found much of it impenetrable. I recently read the entire book and still found sections of it, if not impenetrable, then at the very least difficult to understand and absorb. I found myself having to re-read many sentences, and even entire pages, to fully comprehend what Otto was describing. And I really wanted to understand it all because I knew deep in my heart that it was of great value and importance, perhaps now more than ever.

I think part of the reason the book is difficult to understand is due to its origin in the German language and its grammar, which do not always translate easily into English. But another reason is simply because of the subject matter itself. The holy-the entire idea of it that Otto tries to pinpoint and dissect as though under a kind of intellectual microscope-is both simple and complicated. That is, the experience of it, while profound, is simple; writing about it is quite another matter. In other words, Otto claims that we know the holy when we encounter it like we know our own face when we see it reflected back at us, like those women did kneeling at the rock in that church in Jerusalem. But it can be nearly impossible to describe because, as even Otto himself admits, the personal experience of it is almost beyond words. It is, in a word, ineffable.

We may experience the holy but once in our lifetimes or we may have many such experiences, but, in either case, they are always fleeting. Yet, they stay with us. We are changed. Otto calls these fleeting experiences encounters with the "numinous", a word that Otto coined from the Latin word numen, or divine power, in a similar way that we get the word "ominous" from the Latin word "omen." Otto described it as a "creature-feeling" or creature-consciousness. Here are Otto's own words to define this divine power:

"The feeling of it may at times come sweeping like a gentle tide, pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship. It may pass over into a more set and lasting attitude of the soul, continuing, as it were, thrillingly vibrant and resonant, until at last it dies away and the soul resumes its 'profane,' non-religious mood of everyday experience. It may burst in sudden eruption up from the depths of the soul with spasms and convulsions, or lead to the strangest excitements, to intoxicated frenzy, to transport, and to ecstasy. It has its wild and demonic forms and can sink to an almost grisly horror and shuddering. It has its crude, barbaric antecedents and early manifestations, and again it may be developed into something beautiful and pure and glorious. It may become the hushed, trembling, and speechless humility of the creature in the presence of-whom or what? In the presence of that which is a mystery inexpressible and above all creatures."

Individual experiences such as these are invaluable because they reveal to us where we stand in the universal and eternal scheme of things: that we are small and insignificant; that we think we know so much but actually know so little. This is an inescapable conundrum of the human condition for those of us with the insight and courage to admit it. Yet, at the same time, these encounters of the holy also impress upon us the capacity to sense and cooperate with a divine authority above all others. We might call this a process of discernment. And it is both liberating and troubling. Once we have had an experience of the divine it should come as no surprise that we can then recognize evil.

And it's these powers of discernment and divine authority that the contemporary transhumanists stalking the world-just like all dictators throughout history-want to eradicate from us so they can manipulate us and capture us in the physical and virtual web-think of 5G and 6G technology and AI for starters-of their satanic malfeasance. If we lose our connection to the holy, we lose an essential feature of our human nature-our capacity for discernment and our connection to that which is transcendent. Otto himself says as much: "Its disappearance would indeed be an essential loss." But not only that. Without the holy as a constant presence in our lives we put ourselves at the mercy of those who want to control us, and they are closing in.

Sadly, I think a lot of people have either forsaken this capacity in themselves or have never even known it and, as a result, have unwittingly or enthusiastically given themselves over to the long-running takedown of Western civilization, the final assault of which got underway in 2020 with the COVID-19 psyop, and which is continuing in a myriad of ways today, right up to the recent and fraudulent "No Kings" demonstration that spilled out into streets all over America, funded by-unbeknownst to the riled up participants-as James Howard Kunstler points out, "Shanghai-based software billionaire Neville Roy Singham, Walmart heiress Christy Walton, Paypal partner (and Linked-in founder) Reid Hoffman, and father-and son team, George and Alex Soros." The demonstrators and their backers are much the same coterie who badgered us to "trust the science" and line up to get injected with a so-called vaccine that, as it turned out-and as many of us knew from the get-go-is a bioweapon designed to control and maim and kill us.

I am loathe to give any globalist a fraction of an inch of this column, but we need to know their agenda, and it's been stated in no uncertain terms by Yuval Noah Harari, a key advisor of that demonic alliance, the World Economic Forum:

"Some governments and corporations, for the first time in history have the power to basically hack human beings. There is a lot of talk about hacking computers and hacking smart phones and hacking bank accounts, but the big story of our era is the ability to hack human beings. And by this I mean, if you have enough data, and computing power, you can understand people better than they understand themselves, and then you can manipulate them in ways which were previously impossible. And in such a situation, the old democratic systems stop functioning. We need to reinvent democracy for this new era in which humans are now hackable animals. You know, the whole idea that humans have a soul and spirit and they have free will and nobody knows what's happening inside me so whatever I chose, whether in the election or whether in the supermarket, this my free will, that's over."

It's not over, I'm here to say, and it will never be over as long as we summon the strength from within to not only turn off in every way possible the globalist's attempts at "hacking" our minds and bodies and souls, but also by developing and maintaining our capacity to remember the holy. The holy is the foremost antidote to the transhumanist toxicity. But the holy is not something we do. It is something we experience; it's something that happens to us. It cannot be taught. It cannot be bought. It can only be awakened in the mind, Otto insists, as "everything that comes 'of the spirit' must be awakened." Perhaps most important, according to Otto, it is something that is felt. And this feeling for the numinous is an experience of the divine that, Otto maintains, eludes comprehension in rational terms. We can set out to find it. But more often than not, the transcendent finds us. And it goes way, way back. Otto writes:

"It first begins to stir in the feeling of 'something uncanny', 'eerie', or 'weird'. It is this feeling which, emerging in the mind of primeval man, forms the starting-point, for the entire religious development in history.... And all ostensible explanations of the origin of religion in terms of animism or folk-psychology are doomed from the outset to wander astray and miss the real goal of their inquiry, unless they recognize this fact of our nature-primary, unique, underivable from anything else-to be the basic factor and the basic impulse underlying the entire process of religious evolution."

Christ's agony in the Garden of Gethsemane perfectly encapsulates this holy awe. It is in light of this ancient numinous experience that we can begin to comprehend the import of this agony. Otto writes: "Can it be ordinary fear of death in the case of one who had had death before his eyes for weeks past and who had just celebrated with clear intent his death-feast with his disciples? No, there is more here than the fear of death; there is the awe of the creature before the mysterium tremendum, before the shuddering secret of the numen." The women I saw weeping at the stone in the Basilica of Agony seemed to me to have felt this essential and ungovernable "awe of the creature" that Christ must have felt 2000 years ago.

As I watched those women, I felt a little envious of them. I longed to feel what I believed they felt, to trade in the critical and exegetical machinations of my mind for the simple yet profound embodiment of Christ's passion. When we recall that agony, either there at the rock where Jesus prayed, like those women, or at the altar of the holy feast of the transubstantiated bread and wine, or anywhere else for that matter-when we recall those final hours of the earthly life of Jesus, as he commended us to do during what we call the Last Supper, we unite his agony with our own. It is the agony experienced by anyone who stands up to despots and their evil diktats in the struggle for the individual human sovereignty divinely bestowed upon each of us at birth, nay, even at the moment of our conception.

The Idea of the Holy has had many admirers over the years, including from the very outset the prominent Swiss psychologist, C.G. Jung; the renowned Romanian historian of religion and philosopher, Mircea Eliade; and the celebrated British Christian apologist, C.S. Lewis. Other prominent figures who claim to have been influenced by Otto's work include Mohandas Gandhi, Aldous Huxley, Martin Heidegger, and Ernst Jünger.

In his 1938 book, Psychology and Religion, Jung defines the numinous as "a dynamic existence or affect, not caused by an arbitrary act of will." He goes on to say, "On the contrary, it seizes and controls the human subject, which is always its victim than its creator. The numinosum is an involuntary condition of the subject, whatever its cause may be.... The numinosum is either a quality of a visible object or the influence of an invisible presence causing a peculiar alteration of consciousness." All told, for Jung, the solution to all our dilemmas is found through an encounter with the numinous. Jungian analyst James Hollis writes in his book, Living Between Worlds: Finding Personal Resilience in Changing Times: "Until we can find that which links us to that which transcends us, in whatever arena we may find it, we will be torn apart... until then, our conflicts have brought us only suffering without meaning."

In the opening paragraph of Eliade's notable 1957 book, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, he praises the original point of view that Otto offers:

"Instead of studying the ideas of God and religion, Otto undertook to analyze the modalities of the religious experience.... Passing over the rational and speculative side of religion, he concentrated chiefly on its irrational aspect. For Otto has read Luther and had understood what the 'living God' meant to a believer. It was not the God of the philosophers.... it was not an idea, an abstract notion, a mere moral allegory. It was a terrible power, manifested in the divine wrath."

In his 1940 book, The Problem of Pain, Lewis offers an extensive depiction of the numinous:

"Suppose you were told there was a tiger in the next room: you would know that you were in danger and would probably feel fear. But if you were told 'There is a ghost in the next room,' and believed it, you would feel, indeed, what is often called fear, but of a different kind. It would not be based on the knowledge of danger, for no one is primarily afraid of what a ghost may do to him, but of the mere fact that it is a ghost. It is 'uncanny' rather than dangerous, and the special kind of fear it excites may be called Dread. With the Uncanny one has reached the fringes of the Numinous. Now suppose that you were told simply 'There is a mighty spirit in the room', and believed it. Your feelings would then be even less like the mere fear of danger: but the disturbance would be profound. You would feel wonder and a certain shrinking-a sense of inadequacy to cope with such a visitant and of prostration before it.... This feeling may be described as awe, and the object which excites it as the Numinous."

Not all encounters with the numinous are dreadful and disturbing; not all are, as Eliade writes, "manifested in the divine wrath." They can also be serene and sublime. Otto writes of such encounters:

"The awe or 'dread' may indeed be so overwhelmingly great that it seems to penetrate to the very marrow, making the man's hair bristle and his limbs quake. But it may also steal upon him almost unobserved as the gentlest of agitations, a mere fleeting shadow passing across his mood. It has therefore nothing to do with intensity, and no natural fear passes over into it merely by being intensified. I may be beyond all measure afraid and terrified without there being even a trace of the feeling of uncanniness in my emotion."

In The Problem of Pain, Lewis offers what he believes to be the finest example of just such an encounter from the English Romantic-era poet, William Wordsworth, who describes in the first book of his "Prelude" a scene of rowing on a lake one evening in a stolen boat. In the middle of the lake in the quiet of the night, Wordsworth writes:

<i>There hung a darkness, call it solitude Or blank desertion. No familiar shapes Remained, no pleasant images of trees, Of sea or sky, no colours of green fields; But huge and mighty forms, that do not live Like living men, moved slowly through the mind By day, and were a trouble to my dreams.</i>

There's another scene in the fourth book of that "Prelude" that to me speaks of the numinous as an experience not of dread-not "a trouble to my dreams"-but of sublime beauty. It reads thus:

<i>And homeward led my steps. Magnificent The morning rose, in memorable pomp, Glorious as e'er I had beheld-in front, The sea lay laughing at a distance; near, The solid mountains shone, bright as the clouds, Grain-tinctured, drench in empyrean light; And in the meadows and the lower grounds Was all the sweetness of a common dawn- Dews, vapours, and the melody of birds, And labourers going forth to till the fields. Ah! need I say, dear Friend! that to the brim My heart was full; I made no vows, but vows Were then made for me; bond unknown to me Was given, that I should be, else sinning greatly, A dedicated Spirit. On I walked In thankful blessedness, which yet survives.</i>

I took a seminar in college on the English Romantic poets and it was one of my favorites. I still have the textbook, a thick volume, underlined (of course) in many places and whose spine is cracking from all the use I've made of the book over all these years, and from which I copied the lines above. One of the lines from the second example that struck me then and still strikes me today is this:

<i>I made no vows, but vows Were then made for me....</i>

Numinous moments-always unexpected yet sometimes invited or evoked or sought after-change us, set us off in directions we had not previously anticipated. They come and they go. Yet, as Wordsworth knows-and we who have had such encounters know-they yet survive. They live within us and guide us through the rest of our days, help us discern between right and wrong, good and evil, beautiful and ugly. Or, in the first example of Wordsworth's poem, they haunt us. In either case, they become encoded within us and shape who we are in such a way that they cannot be taken from us. And that's a good thing.

I've begun to wonder if these authoritative powers of self-knowledge and discernment and divine authority-what we read in the Letter to the Ephesians as the "armor of God"-can intuitively alert us to the tempting but heinous provocations of illusion and false promises of those wolves in sheep's clothing that Jesus warns us about, of which the profane realm is chockfull at every turn. And of which we most recently endured in spades during the COVID-19 psyop: Two weeks to stop the spread; masks protect you and those around you; social distancing keeps everyone safe; the school closures, the shutting down of businesses (although, curiously, big box stores and liquor stores were allowed to remain open); the closing of public parks and beaches was for the common good; the COVID-19 vaccines (which were not vaccines) are safe and effective.

Truly, never has there been a greater and more destructive payload of lies rained down upon the human race. I did not fall for these lies and I know many others who did not. And I wonder if having had an initiatory experience of the numinous at some point in our lives-and being attuned to the transcendent as a result-helps us see through the lies of those trying to sell us false promises, be it concerning a used car, a so-called vaccine, or even a way to God. Which is to say that we know Kool-Aid when we see it. And we refuse that cup knowing it is a sham. Or, worse, poison. And perhaps this explains why it's been so hard for us to get through to others who bought and embraced the lies-and continue to do so. They simply don't know what the rest of us know. Which gives us no reason to gloat but rather an opportunity to understand.

There are dozens upon dozens of numinous moments described in both the Old Testament and New Testament. In that time and place they seemed to be everywhere and they permanently shaped the people who encountered them. Let's recall, for example, the legendary example of St. Paul's conversion on the road to Damascus. It so shattered him that he was blind for three days. It is a pivotal event in the New Testament, marking the transformation of Saul of Tarsus, a fervent persecutor of Christians, into Paul the Apostle, one of the most influential figures in early Christianity and whose impact remains to this day. Here's an account of that moment from Acts 9:1-9:

1 Meanwhile Saul, still breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the Lord, went to the high priest 2 and asked him for letters to the synagogues at Damascus, so that if he found any who belonged to the Way, men or women, he might bring them bound to Jerusalem. 3 Now as he was going along and approaching Damascus, suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. 4 He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?" 5 He asked, "Who are you, Lord?" The reply came, "I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting. 6 But get up and enter the city, and you will be told what you are to do." 7 The men who were traveling with him stood speechless because they heard the voice but saw no one. 8 Saul got up from the ground, and though his eyes were open, he could see nothing; so they led him by the hand and brought him into Damascus. 9 For three days he was without sight, and neither ate nor drank.

Or we can go further back in time in our Judeo-Christian roots to the biblical account of Moses' several encounters with God on Mount Sinai—not the least of which was God's deliverance of the Ten Commandments—where on this pilgrimage of mine to the holy land I had also gone. Or at least that was my intention.

Sitting in my small hotel room in the Old City of Jerusalem and looking at my battered copy of the Let's Go guidebook I'd brought with me, I could see it would not be an easy trip to Mount Sinai, yet it was also a place I knew I wanted to experience. I felt then that I was not going to travel halfway around the globe and pass up this opportunity, thinking that I'd probably never return to this part of the world ever again. It was, in no uncertain terms, now or never.

I took a public bus from Jerusalem south to Eilat and then walked across the Taba border town into Egypt, where I negotiated the three-hour taxi ride with a couple of other travelers to Saint Catherine's Monastery deep in the Sinai Desert and at the foot of Mount Sinai. Founded in 527 CE by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, the building of the monastery dates from 530 CE. Back in Jerusalem, I had called ahead to reserve a room in the monastery's guesthouse and was looking forward to walking up to the top of Mount Sinai to watch the sunrise.

The next morning, I awoke before dawn to get underway before the heat of the day. As I was getting ready, I heard the low thrum of diesel engines and looked outside the room's window into the dark to see several buses and hordes of tourists in the shafts of headlights shuffle off them and await orders from their tour guides. I was crestfallen. I guess I should have known. Mount Sinai has been a pilgrimage site since the Middle Ages. Even so, this was not what I expected nor wanted. I had not come all this way on my own to find myself among a swarm of prattling tourists pouring out of air-conditioned tour buses. I wanted to be alone as much as I could be. I could tolerate a handful of others but this was completely out of the question.

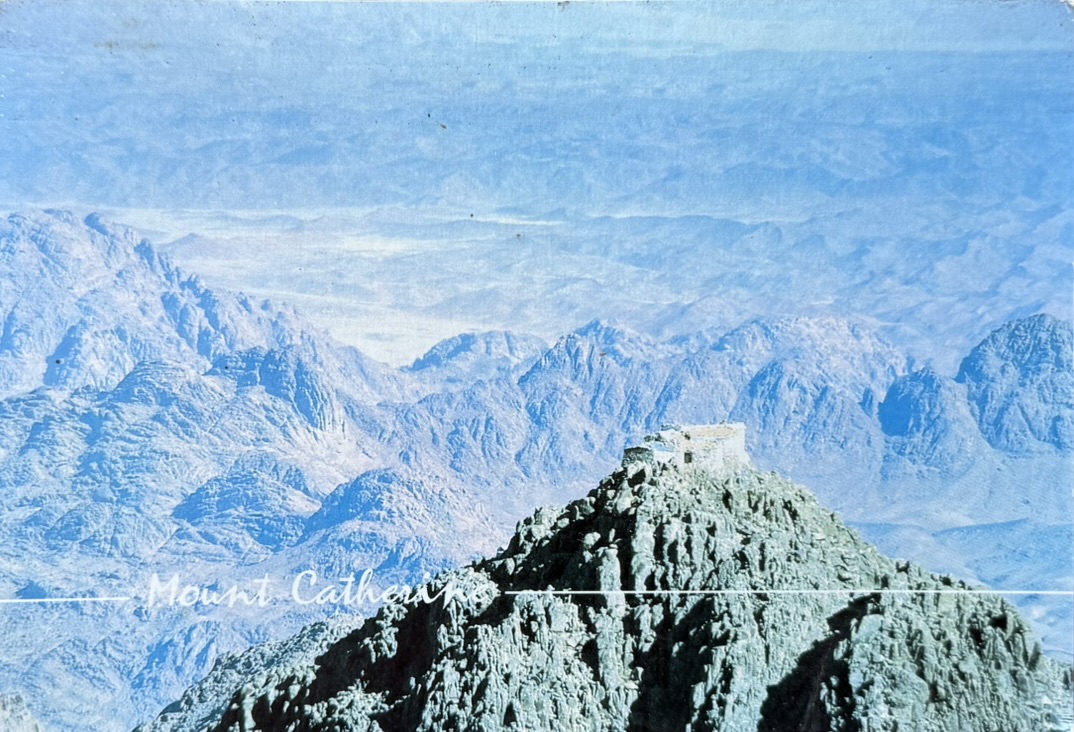

I opened my Let's Go book and read about a climb up another mountain nearby, Mount Catherine. At 8,668 feet high, Mount Catherine is the highest mountain in Egypt. The name is derived from the Christian tradition that angels transported the body of the early 4th-century martyred Saint Catherine of Alexandria to this mountain. At the summit of the mountain there is a small chapel built in 1905 dedicated to her. This was not as important to me as was the opportunity to experience these ancient and sacred grounds without being surrounded by any crowds, even here in the desert. The book instructed that guides are needed to climb that mountain, so later that morning I asked the guesthouse manager how I could arrange such a thing.

"You have to speak to Sheikh Musa," he said.

"Who is Sheikh Musa?" I asked.

"Everybody knows Sheikh Musa," the manager said.

"How can I find him?"

The manager arranged a taxi to take me into the small village to see him. Sheikh Musa's office was simply arranged with a metal desk, a buzzing fluorescent strip light overhead, a few file cabinets, and a map of the Sinai Desert on a wall. He asked me in broken English where I wanted to go and I told him. He said I would need two guides and a camel to carry enough food and water. He told me the price and it seemed reasonable. Then he dialed the phone on the desk to speak to whomever he was hiring to lead me up the mountain. A couple hours later, one of the guides, an older man, showed up. Sheikh Musa told me that the other guide and the camel would meet up with us later that day. Then, the guide and I set off for what would be two nights and three days up the mountain and back down again.

Mount Catherine as seen from the top of Mount Sinai. It is the highest mountain in Egypt. The name is derived from the Christian tradition that angels transported to this mountain the body of the martyred Saint Catherine of Alexandria. At the summit of the mountain there is a chapel built in 1905. It is barely visible at the top near the center of this photograph. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

After a long, hot day we made camp in the open, desert air. There was a cool breeze and I was glad for that. The sun was setting but Mount Sinai and the valley below it were still blazing in full sun. We had met up with the other guide, a younger man with the camel, a few hours before when we'd stopped in a Bedouin camp. We sipped on mint black tea and Turkish coffee while sitting upon woven rugs in the shade a thick woolen tent. Now, a few hours after that, we'd stopped for the night. The younger guide had disappeared with two empty burlap sacks and returned a short while later with those sacks full of firewood to cook our meal, although where he found the wood in such a bare landscape seemed almost like a miracle of loaves and fishes. As we ate there was little conversation. The older Muslim guide spoke no English, the younger one spoke a little, and I spoke not a word of Arabic.

That night we slept in the open. The silence was immense. And in the arid desert sky, the billions of stars were aglow and shimmering as I'd never seen them before. I sat and gazed at them in wonder and at the dark shadow of Mount Sinai. But all was not well. During the day, I'd started having dizzy spells. Now, when I laid on the ground on my back, I felt as if I was going to be spun off the spinning earth, as if there wasn't enough gravity to hold me down. It was strange and quite frightening. There were moments when the feeling was so intense I rolled over and lay my palms on the earth as if that would keep me from being flung into space. The most frightening thing of all was that there was no way out, nowhere to go, to escape this feeling.

The next day was also hot and the trail up the mountain became steeper. The camel stalled several times, refusing to go another step until the guides yanked on its harness. I felt badly about that and about making the guides take me on this trek. Maybe this wasn't such a good idea, after all. I was having dizzy spells like I'd had the night before, not from thirst or from the heat but from the heights we were reaching and from the rocky barrenness that lay all around me. The Sinai is not made of rolling hills of sand, like the Sahara. Most of it is stone and barren, like we see in photos of the moon or other planets. I've never been amidst anything like it before, nothing so alien to me and inhospitable. We trudged on, the younger guide first, then the camel, then the older guide, and then me. At the base of the summit of Mount Catherine, the guides set up camp in a roofless stone hut, spreading the thick woolen blankets for us to sit and sleep on. The younger guide who had gathered firewood the evening before performed his miracle again now.

While the guides prepared our meal, I headed to the summit on my own. It was a short distance away, as far as I could see. Maybe a half-hour's climb. When I reached the summit the vast desert far below me below me came into view. I could only glance at it. I was afraid to face it. It was too high, too much, too soon. My head was really spinning. I feared I might fall. I tentatively approached the small chapel. It was made of stone and mortar with a corrugated metal roof held down by stones and chunks of the clay tiles that had been its roof. I checked the door. It was locked. I walked around its permitter. It appears to sit so precariously upon the mountain top that it seemed to me as though it, too, might tumble down the mountainside at any moment.

I sat down among the rocks and felt I had to hang on to them as if to keep myself from falling, although I was nowhere near any place where I could fall. Sometimes I had to close my eyes just to blot out the terrible beauty of the nothingness that surrounded me, of the vast and incomprehensible age and limitless space of the universe. I felt like I did the night before, only it was more intense now, as if in this short time in the desert my soul was throwing off all ties to the material world. I felt I was going to be hurled off this floating world and there was still nowhere to go to escape that feeling. I searched for—longed for—solid ground, even though I was already on it. I imagined the mountain crumbling beneath me, even though the mountain had been there for eons.

I gamboled on the rocks like a frightened monkey, like those warring apes in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey that had, awakening from their slumber one morning, and gathered around that eerily resonating monolith, fearful yet curious and drawn to touch it. Here was perhaps a similar fear in me, a fear of the unknown, a fear of the mysterious, a fear of that which many of us call God. For the apes, all of that manifested in the smooth, gray monolith that seemed to have either grown up from the ground or to have landed from somewhere else. For me, it appeared deep in my being as nothingness, no existence. No chapel. No mountain. No desert. No people. No planet. No me. It was all a mirage. I don't know what I looked like to the two guides when I returned to the camp when our meal was ready. But I felt spooked by something I'd never felt spooked by before.

The next morning, I arose before dawn and with a flashlight and climbed back up to the summit to watch the sunrise. I wasn't done doing whatever it was I felt I needed to do, whatever it was I had come here to find. When I arrived what I saw in the misty blue light below appeared to me like the bottom of a vast ocean whose waters have long dried up. Or were still there and I was at the bottom. It was simply a different sort of ocean from those we are accustomed to seeing. A desert ocean. My head was reeling again, from the height and from the sensation of motion that I could not stop. And who knows what else. Here was a feeling of the oceanic, all around and within me. My mind reeled backward and forward so much that I felt like I was both everywhere and nowhere at the same time. The past seemed like a dream. The future did not exist. The guides who led me here were not here; they were ghosts and they were gone, spirit guides inhabited by ordinary looking people who'd given me up for dead and left.

I'd taken a blanket with me from our encampment below to keep me warm in the cold desert morning wind. I wrapped it around me now and sat on a rock. I imagined I looked like just another rock. I gazed all around. I felt like I was looking at the beginning of time or the end of it. Miles below, I could see the twinkling lights of the village of Saint Catherine, like the stars in the night sky. The night was hanging on to its last moments. The sun appeared as a thin, orange line on the vast eastern horizon, tracing the curve of the earth. Daybreak was near. There was a faint fingernail of a moon hanging above the sun, the two great lights of the created world, one emerging and the other fading, the cosmic drama of birth and death endlessly repeated and now here before me in full, unobstructed display.

The sun rose higher and the light of the moon faded as the sky became brighter. Then all at once sunlight broke over the desert like molten lava, as if the innards of the earth and the sun above suddenly fused in a flood of heat and light. Then God said, "Let there be light"; and there was light. I glanced across the miles to Mount Sinai and then saw something peculiar until I realized what it was: dozens of tiny flashes from the cameras of a horde of tourists photographing the rising sun. And there I was gloriously—and awesomely—alone. And yet not. There was a presence beyond what my senses could detect or any words I write here can adequately describe. Because there are no words to describe it. Because it doesn't even have a name. Ultimately, the only way that I can describe this experience—the only way that anyone through the ages has been able to describe any experience of the holy—is by stating what it is not. The most we can say is that it is neither this nor that.

A postcard I bought at Saint Catherine's Monastery depicting a bird's eye view of Mount Catherine and the chapel on its summit in Egypt's Sinai Desert.

***

Not satisfied in limiting his explorations of the numinous to Christianity, Otto traveled to many other parts of the world inhabited by those who practiced other religious traditions. In fact, it was an experience he had far away from his home that might have sparked the ideas that were to find their way into The Idea of the Holy. In 1911 and 1912, he traveled extensively in North Africa. A biographer of Otto, Philip C. Almond, writes in his 1984 book, Rudolf Otto: An Introduction to his Philosophical Theology: "Otto's conviction of the centrality of 'the Holy' was aroused by an experience of synagogue worship at Mogador (now Essaouria) in Morocco." Otto described that experience in one of his travel letters:

"It is Sabbath, and already in the dark and inconceivably grimy passage of the house we hear that sing-song of prayers and reading of scripture, that nasal half-singing half-speaking sound which Church and Mosque have taken over from the Synagogue. The sound is pleasant, one can soon distinguish certain modulations and cadences that follow one another at regular intervals like Leitmotive. The ear tries to grasp individual words but it is scarcely possible and one has almost given up the attempt when suddenly out of the babel of voices, causing a thrill of fear, there it begins, unified, clean, unmistakable: Kadosh, Kadosh, Kadosh, Elohim Adonai Zebaoth Male'u hashamayim wahaarets kebodo! (Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Hosts, the heavens and the earth are full of thy glory.)"I have heard the Sanctus Sanctus Sanctus of the cardinals in St. Peter's, the Swiat Swiat Swiat in the Cathedral of the Kremlin and the Holy Holy Holy of the Patriarch in Jerusalem. In whatever language they resound, these most exalted words that have ever come from human lips always grip one in the depths of the soul, with a mighty shudder exciting and calling into play the mystery or the other world latent therein. And this more than anywhere else here in this modest place, where they resound in the same tongue in which Isaiah first received them from the lips of the people whose first inheritance they were."

After North Africa, Otto traveled to India, where he wandered among Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims, and Parsees. In Rangoon (now known as Yangon) in Myanmar (then called Burma), he encountered Burmese Buddhism. He then went to Thailand, where he steeped himself in Theravadin Buddhism. Then on to Japan, where he steeped himself in Zen Buddhism. Otto was the first German scholar of religion to visit Japan's Zen monasteries. Almond writes:"This personal experience enabled him later to see such meditation as a means of experiencing the nonrational essence of the Holy."I can vouch for that. One time a few years ago at a meditation center in Massachusetts, at the end of nine days of silent meditation, I opened my eyes to see dust motes dancing in beams of sunlight coming through a window, and for just a fleeting but memorable moment I experienced much of the same awesome wonder of being in a time out of time that I had experienced years before on the summit of Mount Catherine.

After Japan, Otto spent two months in China familiarizing himself with Taoism. He then returned to Germany on the Trans-Siberian railroad.

Later in his life, Otto continued his travels. In 1927 and 1928, he returned to India and then went to Sri Lanka (what was then Ceylon), Turkey (what was then part of Asia Minor), Israel (what was then Palestine), and the Balkans. These additional travels continued to inform Otto's idea that encounters with the holy, the numinous—that nonrational core experience of transcendence—is universal among the world's religious traditions. Additionally, he taught himself Sanskrit to translate into German the whole of the Bhagavad-Gita and the Katha Upanishad, two hugely important Hindu scriptures.

Yet, despite his world travels and immersing himself in many religions of the world, and acknowledging each their own unique value, Otto—the twelfth of thirteen children born into a religious household and who never married—remained a devout Lutheran his entire life. And he claimed that Christianity"stands out in complete superiority over all its sister religions."Otto writes:

"For what makes Christ in a special sense the summary and climax of the course of antecedent religious evolution is pre-eminently this—that in His life, suffering, and death is repeated in classic and absolute form that most mystical of all the problems of the Old Covenant, the problem of the guiltless suffering of the righteous, which re-echoes again and again.... Christian religious feeling has given birth to a religious intuition profounder and more vital than any to be found in the whole history of religion."

This is the way of the world—the eternal struggle between tyrants and the rest of us—and the way out of the world. That is, to be in the world but not of it. Those of us who have stood our ground and carried the cross of our divinity as we fought against the COVID-19 madness suffered—and in many ways continue to ache from the repercussions of that ruthless insanity—in kind with Christ, guiltless yet righteous. Although the word "righteous"today carries some arrogant, high and mighty connotations, it has always meant nothing less and nothing more than to be right with God. As Christ was. And as many of us aspire to be as we struggle in every way against the mighty forces of evil that would have us all killed or enslaved, again and again. Born of a long line of Hebrew prophets, Christ was first to rise to the momentous occasion of defying anyone and anything that stood between him and God, even unto his sacrificial death. By doing so, he lived an unfettered life, and each of us—no matter what religion we practice or if we practice no religion at all—would do well to follow his lead.

***

As Otto's scholarly career was taking off—in 1917, the year The Idea of the Holy was published, he was offered a chair in Systematic Theology at the University of Marburg and, in 1923, he was invited to deliver a series of lectures at Oberlin College in Ohio, which formed the basis of his book Mysticism East and West—his personal life and health were going in the other direction. In the early 1930s he had to forgo a series of talks he was going to deliver as part of the prestigious Gifford Lectures in Scotland (the list of renowned presenters includes Hanna Arendt, Paul Tillich, Albert Schweitzer, Reinhold Niebuhr, Iris Murdoch, and Karl Barth) because of his increasingly ill health. In 1936, he had an attack of influenza that waylaid him for months.

His death on March 6, 1937 at the age of 67 came as a result of tragic and mysterious circumstances. Some say he died as a result of complications from injuries he sustained from a failed suicide attempt. I'll let Almond, in his book, Rudolf Otto: An Introduction to his Philosophical Theology, have the final word:

"The immediate cause of his death was pneumonia which he contracted some eight days after entering the psychiatric hospital in Marburg. Allied to this was severe arteriosclerosis which was subsequently shown to have begun twenty years before.

"Otto had entered the psychiatric hospital in order to overcome morphine addiction. He had been treated with morphine in order to alleviate the pain resulting from an accident five months before. In early October, 1936, Otto had hiked—alone, uncharacteristically—to Staufenberg, near Marburg. After making a strenuous climb to the top of a manor-house tour, he fell some sixty feet.

"The causes of this event are unclear, but I believe the evidence points to suicide attempt. The injuries that Otto received—a broken leg and broken foot—do not necessarily show that he had either accidentally fallen, or as has been suggested, suffered a hear attack. Moreover, while it was not impossible for one to fall from the tower, it was nonetheless highly improbable.

"Otto had been subject to periods of deep depression throughout his life. He was depressed at the time of the fall and remained so afterward....

"While in the psychiatric hospital, Otto tried to leave in order to throw himself under a train, as his close Jewish friend Hermann Jacobsohn had done in April, 1933, for fear of being placed in a concentration camp...

"The lack of certainty about what happened at Staufenberg speaks most decisively against the suggestion that it was an accident, for, had it been, one might expect those closest to him to have been aware of that. We can only presume that Otto failed to tell anyone what happened, and in none of his subsequent correspondence is there any account of the event.

"Otto was buried in the Marburg Friedhof with the inscription: "Hielig, Heilig, Helig, ist der Herr Zabaoth."

Holy, Holy, Holy, is the Lord of Hosts.

Rudolf Otto

Note to Readers

I'm writing a book on solitude and loneliness. Tentatively titled A Field Guide to Solitude, it is a book about how to be alone without feeling lonely.

Never before in the history of the world have we been more connected to one another. Yet, never before in the history of the world have so many of us felt so lonely. If this was true before the so-called pandemic, it is even more true now, especially for those of us who saw through the lies and fear-mongering and refused to be injected with an experimental so-called medical product and bristled at the mandates, and as a result lost much of our community of friends and colleagues and family members to one of the darkest, most vile, most widespread scourges in human history.

If this happened to you, rest assured you are in good company. It happened to millions of us, including myself. I often think, and sometimes still get angry about, how it didn't have to be this way if only people had kept their wits about them. And turned off their televisions. But that's not what happened and here we are in a world traumatized and torn asunder.

I'm looking for people who are willing to share their experiences of what happened to them and how they coped after being shunned by friends, family members, work colleagues, and others as you held your ground and refused to be jabbed by what was—and still is—being touted as a vaccine against COVID-19. Were you fired from your job for refusing the jab? If so, what did you do? We're you unable to visit your children or grandchildren or parents or grandparents or siblings on account of the choices you made? What were some of the things people said to you? What did you say to them? And if you did get jabbed against your will or better judgment, did you suffer any side effects? If so, what were (are) they?

Please email me: jimkullander@gmail.com

If I use all or part of what you send me, I will get back in touch with you. I can either use your real name or make something up to protect your identity. Take your time; this is going to be a long-term project that I'll be working on over the next several months.

Thank you so much.

Selected Bibliography

Scripture quotations unless otherwise noted are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible. Meeks, Wayne A., et al. eds. The HarperCollins Study Bible: New Revised Standard Version, with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. New York, New York. HarperCollins, Publishers, Inc. 1993.

Almond, Philip C. Rudolf Otto: An Introduction to His Philosophical Theology. Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The University of North Carolina Press, 1984.

Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Translated from the French by Willard R. Task. San Diego, California. Harcourt Brace & Company, 1959.

Hollis, James. Living Between Worlds: Finding Personal Resilience in Changing Times. Boulder, Colorado. Sounds True, 2020.

Jung, Carl Gustav. Psychology and Religion. New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Press, 1938.

Lewis, C.S. The Problem of Pain. New York, New York. HarperOne, 2001.

Otto, Rudolf. The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry Into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and its Relation to the Rational. Translated from the German by John W. Harvey. London, England. Oxford University Press, 1923.

If you enjoy Underlined Sentences, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber if you've not already done so. Either way, it would mean the world me. Paid subscriptions help support the long hours of research, writing, and editing that I spend on each column. I won't overwhelm you with emails. Because these columns take a considerable mount of time to put together, I'm posting them about once a month.